The common theme of the four films seems, at first, to be the contrast between the destinies of those trapped by the rapid rate of development of cities around the world and those who manage to profit from these changes. They are cinematic tales, describing the changes as experienced by and affecting the individual and they are tales of various views and different opportunities, all depending on social status. They are tales of new contrasts and conflicts that arise in connection with these rapid changes. But, after having seen all four films, several and more general themes emerge. What at first glance appear to be stories specifically tied to certain cities, traditions and problems, become entwined and develop into broader global themes which are the very themes that the city-theory in question is concerned with, and reflects the global development Europe is also experiencing.

The slow and the fast glance

The Shanghai film follows one man, who all his life, through photography, has documented the city in which he lives and thus the changes that have occurred. He seems personally unaffected by and even apathetic towards these changes. He almost appears as a mechanical, neutral observer – a kind of caricatured scientist, who is able to rise above the situation and not reveal his emotions for that with which he is in the midst of. Or perhaps he is living proof that we are unable to process the changes that happen around us.

The photograph provides a distance that protects the photographer from mentally relating to the changes. The photographer himself is even eventually forced to move due to these rapid changes. One expects him to lose his footing and thus the ability to record the developments from an objective standpoint. But he remains in the role as observer. He observes his own moving, as an event similar to all the other events that he observes through photography. The film shows a parallel story about a professor, who is preoccupied with examining how to build very dense cities. An important question in relation to this is, for instance, how will it be possible to create an attractive, green world in underground cities?–or how to create the natural within the artificial? The professor is a contrast to the photographer both in the sense that he doesn’t exist outside time but in the middle of it, and acts within it. He has not resigned himself to the developments, but, on the contrary, sees enormous opportunities in these new conditions. But a more abstract interpretation suggests similarities between the two in that they both maintain a kind of distance to reality – through photography or through computer simulations.

If the photographer had appeared in an American film of the 60s, the explanation for his behaviour would have been attributed to Communism. That explanation could also work in this case, but it could easily become an excuse not to see the quiet person as an expression of more general problems linked to urban life. We can view him as a figure that is in sync with Georg Simmel’s claim that urbanites have to protect themselves mentally against the hectic dynamic of the city by taking on a phlegmatic attitude and hiding behind the observing yet non-committal gaze. We can also see the photographer as an example of Sharon Zukin’s claim that it is not possible to understand the changing city without placing the question in a broad cultural frame of comprehension. The photographer himself embodies certain cultural codes and references that makes him unable to internalise the rapid changes and thus renders him incapable of responding actively.

The life of the photographer in the margins of the reality that surrounds him leads him into Zygmunt Bauman’s conceptual universe and his description of globalization. Bauman believes that physical, social and cultural mobility is essential to act in the globalized world. Bauman distinguishes between those who, due to educational and cultural background, have a high degree of mobility and those who do not. The mobile one is the tourist, who can move physically, socially, and culturally. The immobile one is the vagabond, who can not. The vagabond has to live in isolated spaces in the globalized landscape.

The professor – and by extension architects as a group – become an example of the tourist. But the tourist, with his enthusiasm and ability to act under new circumstances, has in this film a touch of superficiality and lack of ability to understand the social and cultural context – and to see and preserve its qualities.

Mobility

Mobility is both a condition for and an effect of globalization. We have moved the industrial production, which kick-started a period of wealth 100 years ago, to the other side of the world. But the system only works if we transport the goods back to ourselves. And we can only profit from this system if our cultural and social mobility increases.

Simultaneously, we have moved industry within history. We have apparently outsourced it to social and cultural spaces similar to those we had 150 years ago. But in these new industrial spaces static and tradition-bound cultures exist together with Western types of organisations and norms in a way that undermines the picture of a simple time-shift or the re-recording of the history of industrialization. Rather than being re-recordings, the situations we experience in the films are parallel to the tale of a person hurled a hundred years back or forth in time, only to experience the impotence of his time-bound system of knowledge in decoding and interpreting the new reality, and the irrelevance of those values connected to the time period, which formed this very person.

In the West we speak a lot about the importance of physical, social and cultural mobility, as defining features that characterize our adaptation to this post-industrial society. The people that appear in the films are at the same time forced into the same kind of cultural and social mobility but they also find surprising ways to navigate a space that contains many different time-warped life- and culture forms.

Mobility appears in the films both as the liberator and the problem-creator.

We meet the market vendor and his family for whom the car is at once the dream of being able to drive away from the cramped city and the symbol and proof of social mobility.

To the uptown woman, who always has had access to physical mobility, the new car of the market vendor poses an enormous problem. She lives in a rich neighbourhood that is threatened by road expansion. Thus the car of the market vendor becomes a symbol of increased traffic which follows Mumbai’s rise in wealth and which can only be accommodated if the capacity of the infrastructure is improved with larger roads and so-called flyovers at the most strained roads.

The woman heads a group of residents of a well-to-do neighbourhood, who fights against the road expansions and in so doing, symbolically fights against the opportunity of the market vendor, refusing him the very mobility that she herself has always had access to.

Her somewhat starry-eyed, unrealistic and impractical group of activists awkwardly attempts to employ the same actions that traditionally characterized actions of the lower classes, but at the same time they skilfully exploit and use the legal system’s opportunities to complain, delay or prevent the road project. They represent a traditional upper-class, that has lost the ability to understand social dynamics and at the same time they represent the battle for the environment and traditional features of the city landscape. They represent a society which struggles to find the means to control the actual and intimate changes but which has a strong legal machinery to handle classic and broader conflicts with.

Thus the story crosses and ties together many of the themes that are in play in recent debates on climate change and globalization. Western fear that the fast growing Asian economies will throw the ecological balances out of sync, ecological balances that we ourselves have taken to the breaking point, is reflected in the upper-class woman: Sitting in her car with her chauffeur she is at the same time annoyed with and genuinely concerned about the increasing traffic. She takes it for granted that she can drive along in her car but watches with devoted concern the consequences of others, who also want to drive their cars.

The market vendor wants to climb the social ladder – towards a better life for his family and himself. He seeks mobility in the broadest sense; to him social mobility and physical mobility are synonymous. The car becomes the common symbol of social, cultural and physical mobility. From precisely this interconnection, springs one of the most difficult issues regarding the public debate on climate change, because from the market vendor’s point of view it is all about depriving him of his mobility whilst reserving it for the few.

Sanitation

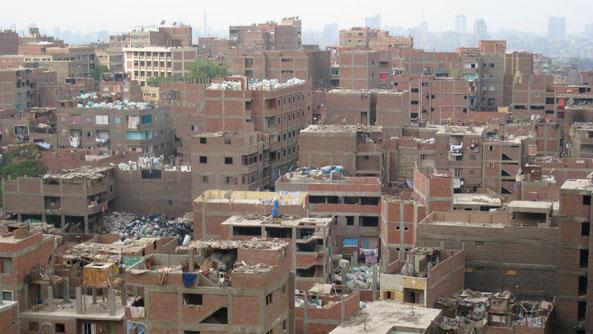

City garbage and the way it is managed is the opening to the story about Cairo. We experience a cross editing of Cairo’s traditional garbage collectors and the entire inventive and sophisticated recycling sector of which they are a part, and the attempt – by Western measures – to make a modern sanitation-system work. The new system is run by a global company with Italian roots.

This new system involves residents taking out their trash to containers, whereas before they had been used to garbage collectors coming to their door to pick up the garbage. This results in what could be described as an absurd, obstreperous, and heroic resistance towards the new system — where the residents throw their garbage in places other than the garbage containers, as in a diffuse and unorganised action, and end up damaging themselves as much as the system and the company they oppose. Simultaneously we see in flashes how the Italian company attempts to solve the task as easiest way possible by referring to an organization that abides by the guidelines set down in management literature. An almost mythical figure appears between these two parties, a figure who arguably represents the grotesque global company in the legal sense but who also represents that which is just or good. He is the one who attempts to make the system work and make the residents act in their own interest. But he becomes the object of hate for both his superiors and residents alike.

While this story about the implementation of the global company unfolds, we witness the disintegration of the old, in many ways a delicate and sophisticated garbage and recycling system. We also see how the garbage collector’s system is totally disabling for many of those who work in it whilst at the same time we regard this system as carriers of a specific culture with its own rituals and norms.

The garbage story is at once very concrete— one can almost smell the garbage and feel the need to protect oneself against the dust, whilst watching the film, and at the same time it is a very symbolic and ordinary tale that brings about many of the themes that occupy the urban debate.

At first glance it seems ironic that it is garbage that proves to be the entry point for Western type organisations and globally acting companies into Cairo. We would like to think that we are the ones bringing high technological expertise that can further the development of this part of the world. And we are inclined to believe that cities like Cairo can independently develop organizational forms within those sectors that require a lot of manpower.

But the Cairo story illustrates three central statements and charts of globalization’s functions. One of the most famous charts shows the flow of electronic products. They are produced in East Asia and sold in the West but the electronic waste is returned to other parts of East Asia. Zygmunt Bauman states in the book cited before that globalization is defined by the absent and irresponsible Lord, which alludes to a comparison between feudalism’s city- based land-owner and our present globally operating companies, that don’t belong anywhere and feel no responsibility for any local areas. The third statement is to be found in Saskia Sassen and Manual Castells’ work, where they describe the cities of the West as control centres for global financial flow and exchanges. What we experience in the film is not a Western company that is primarily interested in organising sanitation, but a company that sells service and organises profit oriented methods. By communicating its abstract organising-models to a local bureaucracy, raised within Western management thought, and which views these solutions as an expression of the most advanced and relevant ways of acting.

We are left with a very striking example of how financial flow control is interconnected to spreading cultural forms.

In the Cairo film we witness what is in many ways a highly developed recycling system that no one has had the ability to develop and modernise because the organizational way of thinking necessary to complete this development project doesn’t exist. In its place, Western knowledge-imperialism has injected susceptibility to Western models and a lack of ability to see the potential in existing styles of organisation.

That garbage export is linked with export of management styles, and that this happens through an Italian company, brings to mind the Italian mafia’s lucrative involvement in this sector.

In the West, we would prefer not to be confronted with the garbage problem because it exposes our mass consumption and some of the methods that we don’t fully control.

The most common dimension in this story is, however, the capacity of globalization to create, through financial and cultural homogenisation, a very conformist thought-space in which, as in this case, it is only possible to think in outsourcing and mass production in Egypt in the same way as it is thought of in Denmark or in the U.S.

Politics

The story about the mayors and the political scene in Bogota is in a weird way, as in the other films, both disturbing and encouraging. On the surface, the film is about a traditional political scene where the politician must fight his way forward both physically and with arguments. It appears as though our sophisticated, media-based political methods have not yet prevailed. In Bogota, you get up on a chair—and if you can’t get attention in any other way, you pull your pants down and bare your arse until you make yourself heard.

In another sense as well, it is seemingly an old-fashioned political scene – the politicians that appear here can in a very concrete way turn opinion around, are enthusiastic and can stick to the issue. But gradually, as this story unfolds, many conditions begin to resemble circumstances common to our media-based political campaign. That which at first glance appears to be a form of political activism rooted in radical grass-roots student movements attain, little by little, the characteristics of a well-contrived and controlled political campaign. And the actual election of the mayor, which at first seems to be 'a new beginning' liberated from internal power struggles of the parties, reveals over time, weaknesses in this fragmented and individualised structure. The successful isolated cases can not last in the long run. And what then left: demagogical populism?

Developed and developing

We usually define Western cities as developed cities and the rapidly growing cities as developing cities. Doing so is logical in the sense that a huge expansion takes place in the latter while in comparison, cities in the West are regarded as fully developed and with little room left for expansion. But the distinction between developed and developing also suggests a conclusion where Western cities are only in a very limited way affected by the forces that change the expanding cities. Finally, let us ask if this suggestion holds – is what the four films portray only something that happens ‘other’ places – or does it also happen here with us, in the developed cities of the West?

After seeing all the films and processing them at a distance you discover, as mentioned before, that as much as they tell the tale of four cities, they also tell the general tale of how globalization and the post-industrial agendas act in some specific social and cultural spaces– and transform them. The question then is if it is only the spaces in upcoming cities that are transformed or whether it, to the same degree, happens in Western cities – but in other ways.

The changing processes of globalisation are indeed global. They are active all over the world but they act very differently depending on which local, financial, social, and cultural structures they encounter.

It is obvious that our political and administrative systems are much better founded and stronger than in most of the cities that the films depict and therefore we can influence the way in which the forces of the globalisation is directed to a much larger degree.

It is also self-evident that it is the Western cities and their financial systems that are the originators of the many transformative methods in play – it is our business cultures and financial models that we spread.

And Western cities are in Saskia Sassen’s words, “control centres of globalisation” – it is from here the globalisation processes and the global networks are controlled.

But do we, then, also have control in the sense that we can avoid or prevent the problems and conflicts described in the films? Or are the forces of globalisation, although they carry our values and cultures, made independent and act as Bauman’s absent Lord – without responsibility for or connection to any place?

In any case, many of the conditions the films describe have thought-provoking parallels to us. And the overall themes: Mobility, Sanitation and Politics can symbolically as well as concretely function as guides to debating relevant phenomena in Western cities.

Mombai—Copenhagen

The Mumbai story about the market vendor’s new car and the upper-class woman’s fight against traffic and pollution in her part of the city is globally seen as the metaphorical tale about the different positions for the coming climate conference – of Western concern about the financial expansion in other parts of the world, and our reservation against limiting our own use of the car, both in the concrete and figurative sense.

The story also has its more local parallels. The market vendor’s touching enthusiasm for the new car is perhaps mainly a parallel to Western cities in the 1950 – and 60s. However, the question is whether, in principle, there is any difference between the controlled enthusiasm that radiates from the one who passes a smart café in his car and with considerable but phlegmatically restrained attention checks if his new Porsche or Aston Martin is noticed by the right people – and the Tatra owner’s joy? The Mumbai film illustrates the dependence of consumerism that we try to spread to the rest of the world. And it is precisely this basic dependence that makes it almost impossible to reduce our energy consumption – and which makes it even more threatening when other parts of the world try to close in on our consumption, despite the fact that exactly this growth is the reason why our global economy can function.

The upper-class woman in Mumbai, quite concretely, fights against the construction of a so-called flyover – a type of bridge that leads part of the traffic above a crossing, hereby increasing the traffic capacity of the crossing. But flyovers can also be seen as symbols of many of the changes and new divisions that globalisation create in both developing and developed cities. We invent more and more communication systems that can divert us away from what we don’t want to face. We have elaborate traffic systems that can take the wealthy middle class around the world from one interesting historical city centre to the next without us ever meeting the poor. And we have the same traffic systems in place internally in the city regions – systems that take the wealthy middle class from their suburbs to their place of work or entertainment in specialized city centres. Flyovers are at once the symbolic and concrete answer to how spatially to divide the city into tourists and vagabonds, as according to Bauman: You make independent and separate networks. The tourists move in one network, which is globally connected. The vagabond moves in another network, which in the physical sense is local. But that also means that we are on our way to reforming or dismantling that which was traditionally seen as a project of the city: to initiate new cultural processes and innovations through the meeting of various groups.

Seen in this perspective the Mumbai-example becomes even more ambiguous, symbolic and general: the upper-class woman fights against the flyover which will increase her mobility and in principle free her from the meeting with the poor because this rising above can no longer happen without affecting her daily life in a negative way.